Phelonise Haydel’s Creole heritage had always been a defining factor of her life. This was particularly true in her old age. By the time she was in her seventies, she was entirely reliant upon the charity of her adopted daughter Philomene and her grand nephews. She had no other means of supporting herself. The money brought in from the sale of the land given as a bounty to her husband for service in the War of 1812 was long gone. There was no way to have made it stretch over three decades. She had to find another way to survive. Once again Jean Baptiste Monplaisir Dangluse’s military service would prove beneficial.

She turned to an attorney named Clarke for assistance. He filed Phelonise’s application for a widow’s pension. J. D. St. Herman and Jacques Meffre Rouzan, Creoles of color who had served with her husband and been close to the family for over sixty years, acted as witnesses on her behalf. Phelonise anxiously awaited money from the federal government for her late husband’s participation in the Battle of New Orleans.

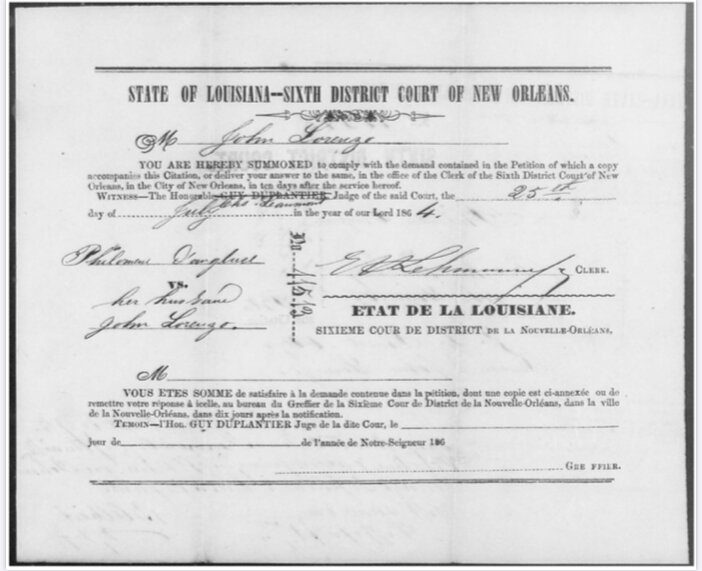

Unfortunately she had a hard fight ahead of her. Pension agents and the federal government were perplexed by Phelonise and her husband’s Creole names. On some records she was Felonise, on others Phelonise. Documents contained the name Monplaisir Dangluse and Jean Baptiste Dangluse. American bureaucrats’ ignorance of the French language and Creole customs jeopardized Phelonise’s chances of ever receiving a pension. Her illiteracy, common amongst elderly formerly enslaved individuals, also prevented her from effectively managing her case.

John Benton, special agent from the Pension Bureau, was tasked with determining the validity of Phelonise’s claim. With Felix Delille acting as his interpreter, Benton began making inquiries in 1881. Benton wrote the following about the case and his interactions with Phelonise Haydel Dangluse:

‘Phi’ in French (so says my interpreter) is pronounced ‘Fe.’ The applicant is old and very poor, and I may add very respectable, and will anxiously await the disposition of her case, hoping that it may be such as will enable her to get out of her present cheerless and uncomfortable quarters into something more befitting her age and enfeebled condition.

I will add that the applicant speaks and understands English so poorly that without the assistance of an interpreter it would be almost impossible to get anything like a correct understanding of her case from her; and this fact may account for the. . .confusion into which her case has been thrown by her attorney Mr. Clarke, who does not appear to understand French, nor engage the services of a clerk or interpreter who does.

This was post-war New Orleans, and the movement toward Americanization was almost complete. Creoles were outnumbered, and French was no longer the dominant language. Over the course of her lifetime, Phelonise had witnessed the flags of Spain, France, the United States, the Confederacy, and, once again, the United States fly over her home. She had observed the city’s evolution from Francophone and Catholic domination to a place where Creoles were struggling to hold on to their culture. They were outnumbered and no longer the cultural and political force they had once been.

Jean Baptiste Etienne Dangluse death certificate, showing that Phelonise was born a Haydel.

The American pension claims agents had been confused by Phelonise’s first name. When Benton questioned her further about her surname, Phelonise’s strong Creole heritage was once again revealed. “[I have] always been addressed and referred to by [my] friends and acquaintances as Madam Monplaisir, in accordance with the custom of the creoles to address a wife or widow by her husband’s Christian name,” Phelonise said on January 13, 1881. It is likely that translator Felix Delille confirmed this tradition.

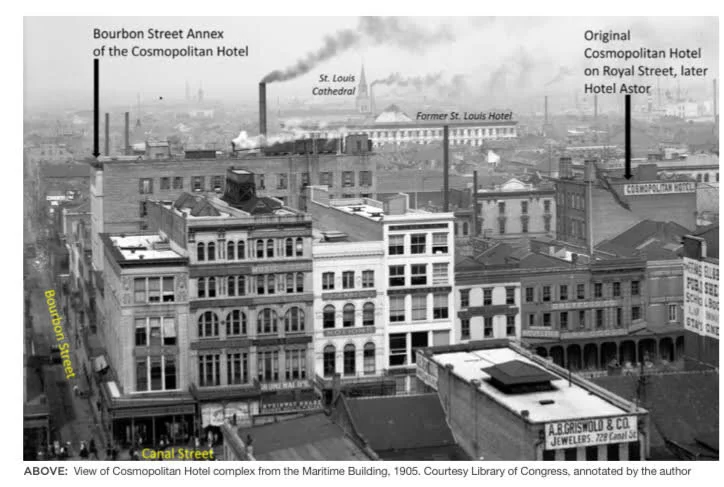

After meeting with Phelonise, John Benton sought out her adopted daughter. Now forty-two and married for a third time, Philomene’s life had gone through its share of twists and turns. Shortly after her divorce, she began a relationship with a French immigrant named Louis Eugene Simonin. They were living together in 1870 when she gave birth to her last child, a daughter she christened Valentine. On February 19, 1874, when Louis Simonin was seriously ill, he and Philomene were married by a justice of the peace. Four days later, she was a widow. Fourteen months after Simonin’s death, Philomene wed Auguste Louis Ostalier. Also a French immigrant, Ostalier had resided with the Simonins, signed as a witness at their marriage, and was close friends with the family. Louis Simonin was the wine bottler at the Cosmopolitan Restaurant, an establishment on Royal Street near Canal that offered “all the delicacies of the season” and “also choice wines of all kinds.” Auguste Ostalier kept the wine cellar there and was involved in a professional organization for waiters and chefs. He soon had Philomene’s sons, George and Jean Baptiste, working in the industry. George was the “pantryman” at the Cosmopolitan, and Jean Baptiste worked there as a laborer.

Image from Richard Campanella. For his excellent article on the Cosmopolitan, see https://richcampanella.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/article_Campanella_Preservation-in-Print_2016_Feb_Cosmopolitan-1.pdf

Pension agent Benton visited Philomene Dangluse Ostalier at her home on Toulouse Street, just a few blocks from where her husband and sons worked. He had questions about her mother. She told him that she had known the Dangluses “from her earliest recollection. . .having been raised from infancy by them.” She remembered witnessing their wedding ceremony, which took place when she was around nine years old. Philomene also explained that since childhood Dangluse “had borne the ‘petit non’ [nickname] Monplaisir. When applying for a bounty he had [me] assist him as [I] could read names and dates both in print and in writing.” Philomene had to “look amongst his papers for his discharge.” She also revealed that his final resting place was in an unmarked grave at St. Barthlomew’s cemetery across the river.

Two months after Phelonise’s case was examined by the pension agent, she celebrated the marriage of her grandson George to Adele Texier. Adele’s mother was a free woman of color and her father a white man from France. He had two families; one with his French wife and children, and the other with Adele’s mother Josephine and her siblings. On January 15, 1882, Phelonise became a great-grandmother and Philomene a grandmother. Anna Bertha Lorenzo was born to George and Adele. Her parents’ birth certificates both had the word “colored” written after their names, but little Anna’s had the word “white.” Beginning in 1870, Philomene and her sons George and Jean Baptiste and daughter Valentine had crossed the color line. For over a decade, legal documents and census records had classified them as white.

Phelonise did not live long after meeting her first great grandchild. She died on May 27, 1882, at her grand nephew Arthur Gayaut’s home in Algiers. She had only been receiveing her pension for a little over a year. Gayaut inquired if the pension could cover some of her final medical bills and funeral expenses.

Soon after the passing of her mother, Philomene became ill with uterine cancer. She died on October 27, 1885, at the age of 47. The deaths of their mother and grandmother severed any connection George, Jean Baptiste, and their little sister Valentine had with slavery and the plantations where their family had been enslaved in St. John the Baptist parish. All three children chose to identify as white. Soon one was contemplating leaving behind family and old memories in Louisiana and making the move to a place where he could leave all trace of his past behind him.