Evergreen Plantation provides an excellent model of the evolution of Louisiana’s slave society from the colonial era into the early national and then antebellum periods. In 1790, upon the death of her husband Pierre, Magdelaine Haydel Becnel opened his succession. An inventory was made of the Becnels’ property. Surviving records document a total of fourteen slaves. All of the Becnels’ slaves were described as negroes (black) with the exception of twenty-six year old Therese, listed as a metis, or of an indeterminate mixture of European and Native American ancestry. Though worth 350 piastres, Therese was “granted her freedom by the authority of a judge due to her Indian heritage,” in keeping with Spanish laws of the time. By 1790, Indian slavery was illegal and was nearing an end in practice.

The Becnels’ also had a family group of slaves, including a mother, Marie Joseph, and her two sons and two daughters, worth together 650 piastres. As ordered by the Code Noir, Marie Joseph and her children were inventoried together and could not be sold separately, as the children appeared to be under the age of ten. Eight male slaves were included in the inventory, valued at a total of 2850 piastres. All possessed French names, with the exception of Tetemac, and ranged from twenty to thirty years of age. None of the men were Creole, or born in the colony. Two were Bambara, two Fulbe/Pular, and the rest of various African groups, including Mandingo, Moor, Soso, and Konkomba. Four shared the Mande dialect or language, while the other four spoke another West African language.

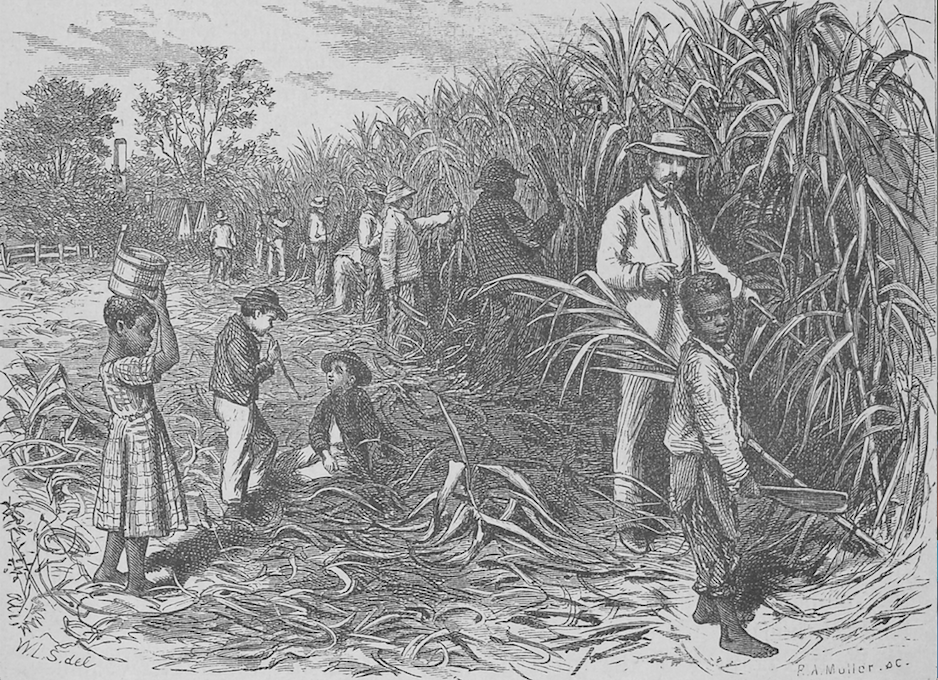

By 1810, Magdelaine Becnel significantly increased her wealth through sugarcane production, a burgeoning new crop due to Etienne de Bore’s successful crystallization of sugar on a commercial scale in 1795. According to the St. John the Baptist parish census of 1810, Magdelaine Becnel owned forty slaves, making her the largest slaveholder of the parish’s twenty-five households headed by women. In the 1820 census, she appeared as “Widow Becnel and Son,” indicating that she had made her son a partner in a plantation that included ninety slaves, seventy-three of whom were engaged in agricultural labor. Thirty of the fifty women on the plantation and twenty-five of the forty men there were between the ages of twenty-six and forty-five. There were ten children of each gender, and ten women over forty-five as compared with only five men over forty-five.

Upon Magdelaine’s death in 1830, a significant portion of her inventoried estate consisted of ninety-four slaves. With twenty-seven female slaves and sixty-seven male slaves on the plantation, the sex ratio was severely skewed. While most of the men worked in the cane fields as carters, plough hands, or laborers, most of the women functioned as domestics, serving as cooks, children’s nurses, washerwomen, and maids. Some of the slaves were afflicted with entropied limbs, including Albert and Lenhem, whose right hands were damaged, and Cloe, whose feet did not function. Several American male field hands were listed as being “fourteen years in the country” or “eight years in the country,” suggesting that they were familiar with the labor associated with a sugar cane plantation and had adapted to life in Creole Louisiana. This detail may have been mentioned to entice buyers to pay more for them, as Creole slaves often fetched higher prices than American.

Of special interest is Sally, a thirty-year-old American negresse who was “good for nothing” and worth only 5 piastres, the lowest priced slave under the age of sixty. Perhaps she was physically or mentally handicapped, considered defiant, or a habitual runaway. Magdelaine’s estate inventory contained another aberration: Sam, a thirty-year-old American griffe listed with his two-year-old child, together worth 400 piastres. Usually slave children were inventoried with their mothers and when a mother was absent due to sale or death, the child was listed alone as an orphan. This child, whose name was omitted in place of the classification “orphan,” was estimated with his father, indicating that they would remain together as a family unit.

Nearly three decades later, Magdelaine’s great-grandson, Lezin Becnel, and his brother Michel were operating the plantation, which now had a work force of ninety-six adult slaves and twenty-one slave children, for a total of 117 enslaved individuals. With sixty-seven adult male slaves and twenty-nine adult female slaves, the sex ratio on the plantation was still skewed in favor of women. In contrast, there were six male children and fifteen female children. Sixteen of these slaves served as domestics, probably managed by Amelia Becnel, Lezin’s wife. Of these sixteen, ten were women, emphasizing that house slaves were typically female. While the slaves’ names remained primarily French, some names indicate the Anglo-American influence and the influx of American slaves, who often had last names from previous owners, including Starling, Tom Brown, and William Boone.

On the eve of the Civil War, the Becnels had amassed $150,000 in real estate and $125,000 in personal property. Evergreen had grown into a major plantation complex and could be considered representative of a typical Creole plantation of its time.